| Title Historic disturbance and vegetation type change, a case study from the Ord Mountains, San Bernardino County, California | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

Author Jim Alford American River College, Geography 350: Data Acquisition in GIS; Spring 2013 Contact Information jim.alford@comcast.net | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

Abstract This is the summary of the entire paper. All the following sections should be represented by a single sentence or two, with the exception of background and references. Write this last. | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

Introduction The Mojave Desert is an ideal location to develop understanding of vegetation patterns. Limited by harsh environmental conditions, vegetation patterns are much simpler than those found in mesic areas. Casual observers may find Mojave shrub lands boring, but these simple patterns lend themselves to easy understanding. Although modern human economic activity came late to the Mojave, it has produced major effects upon vegetation and the degradation of natural communities. At the same time, human -caused disturbances have facilitated a variety of biological invasions. The biological invasions affecting Mojave vegetation come in two forms. Most dramatically, Old World plants such as Schismus sps., Bromus sps and Brassica tournefortii have converted many thousands of acres to semi-natural stands. Semi-natural stands are novel vegetation types that are dominated by exotic species and persist in the wild (Sawyer et al, 2009). However; disturbance may also release native species from limited niches and allow the formation of native vegetation outside its historic niche. A prime example is Ambrosia salsola (cheese bush). It evolved as an early seral type, repopulating washes after flooding events. Today it can be found growing in huge upland stands due to energy and road development, fire and agriculture. Bulldozers, grazing and fire have released it from the washes (personal communication, Keeler Wolf, 2012). | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

Background Elton literally wrote the book on biological invasions in 1959. While others (even Darwin) had described biological invasions, not until Elton was it understood to be a serious environmental threat. This study attempts to fuse Elton’s ecology of invasion with a well-known “law” of geography formulated by Waldo Tobler in 1970: “Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things”. Here an attempt is made to apply Tobler’s law to the geography of Elton’s disturbances. The Mojave Desert was remote until recent times. Nearly all development has taken place since World War II. Excepting desert wetlands, weedy species were rarely found until recently. Red Brome was common in the Mojave by 1950, possibly coincidental to the interstate highway expansion (Sawyer, et al 2009). | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

Methods The first step was base data acquisition. For background imagery NAIP (National Agicultural Inventory Program) 2009 was used. Digital Raster graphics of USGS topographic maps held a wealth of information: mines, pits, utility rights-of- way, roads and buildings. Both of these were availabale through the state of California Cal Atlas. The final and perhaps most important piece was the 2012 vegetation map of the area form California Department of Fish and Wildlife. This map is available through CDFW's gateway. Additional layers were derived from these data. The vegetation map was limited to the three polygons of weedy species. The Digital Raster Graphic was used to digitize several layers including: mines, test pits, utility rights-of-way, and ranches. | |||||||||||||||||||||

| The Generate Near Table was used to access the data. Statistics were generated for each Near Table. The query was the distance to the weedy polygons from each disturbance polygon. Histograms and descriptive statistics were examined and the mean distance by disturbance type was graphed. (R) Mojave Yucca near ord summit |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

Results There were significant differences in the distances from weed

polygons between types of disturbance. Responses broke into two clear groups.

| |||||||||||||||||||||

|

These results offer only a single conclusion. There is a

clear difference in orders of magnitude between the distance to ranches

and all other tested disturbances.If the ranch discontinued in 1944 were

not included in the anlaysis the mean, min and max of ranches would be zero. | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

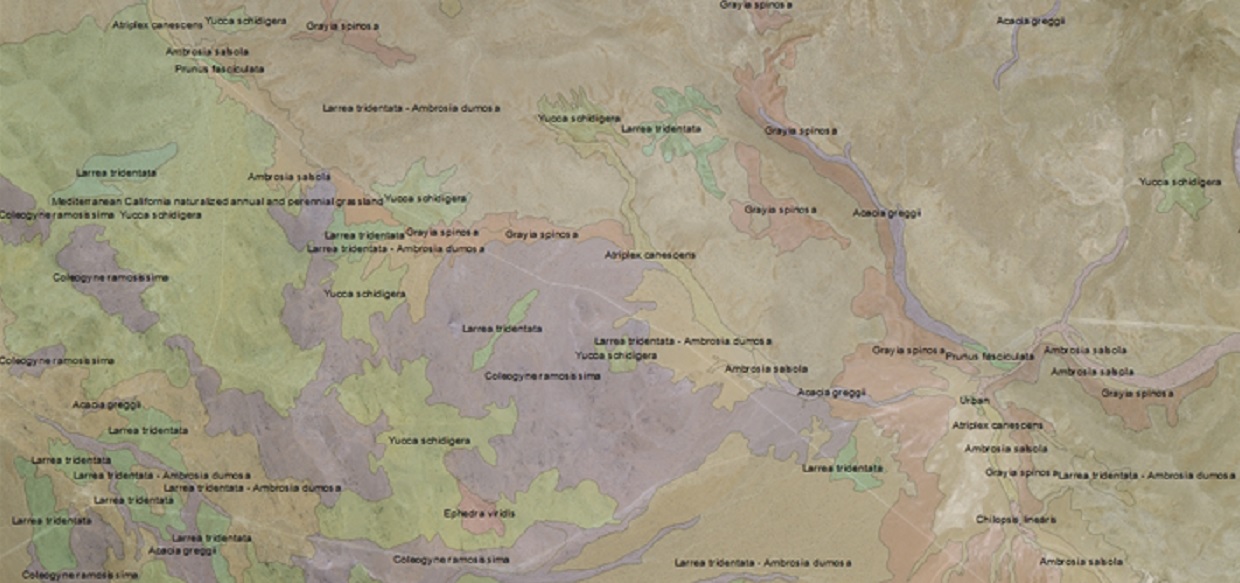

Maps | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

(L) Clip of CDFW vegetation map. | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

Analysis It must be noted spatial autocorrelation is a risk in this type

of study. For example, roads were not consdiered a disturbance due mostly to the difficulty in sorting

actual used roads from WWII military tracks, motorcycle trails and unauthorized ORV tracks. However;all

roads lead somewhere, perhaps a mine, pit, ranch or pipeline. While this model is considerably simplified

from the real world system, it provides information useful in the mental modeling of invasion even many

years after the fact | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

Conclusions It is apparent that his study could be improved by the inclusion

of both fire adapted and fire adverse vegetation types. Recent studies on the decline of Blackbrush

(Coleogyne ramocissima) have spurred federal agencies to take a more aggressive stand on conserving Blackbrush,

a very fire sensitive type.

| |||||||||||||||||||||

|

References Literature cited. California Department of Fish and Wildlife, 2012. California Deserts Renewable Energy Conservation Plan, https://nrm.dfg.ca.gov/FileHandler.ashx?DocumentID=47996&inline=1, accessed 3/5/13.3. Elton, C., 1959. Biological Invasions of Plants and Animals. University of Chicago Press. Sawyer, J., T Keeler Wolf and J. Evens, 2009. Manual of California Vegetation, Second Edition. California Native Plant Society Press, Sacramento. Tobler, W. A computer movie simulating urban growth in the Detroit region. Economic Modelling, 46(2):234-240. | |||||||||||||||||||||